My Oil Pastel Collection: exploring interpersonal beauty & culture

This collection is a discussion of beauty and culture as it relates to my family. Art is often used as a commentary on society, a way to reflect on normalities that we have collectively created. However, for this specific collection, I chose to focus on the more personal side of some of these themes. I have found that viewing them in this light allowed me to see the more positive sides of things. These pieces were a reckoning of topics that I often push away, like otherness, belonging, and beauty as it relates to my Asian American identity. Throughout my process, as well, I questioned what I believed to be the idealized way of creating art. I ended up choosing oil pastels as my medium because they allowed me to be loose with both my linework and my shading. More importantly, this medium allowed me to be more forgiving as it cannot be erased and is difficult to cover up. I had to trust that my mistakes would not tarnish the beauty of the final piece, and only enhance it. In the end, my drawings imitated a kintsugi ceramic, with the imperfections making the piece more enticing.

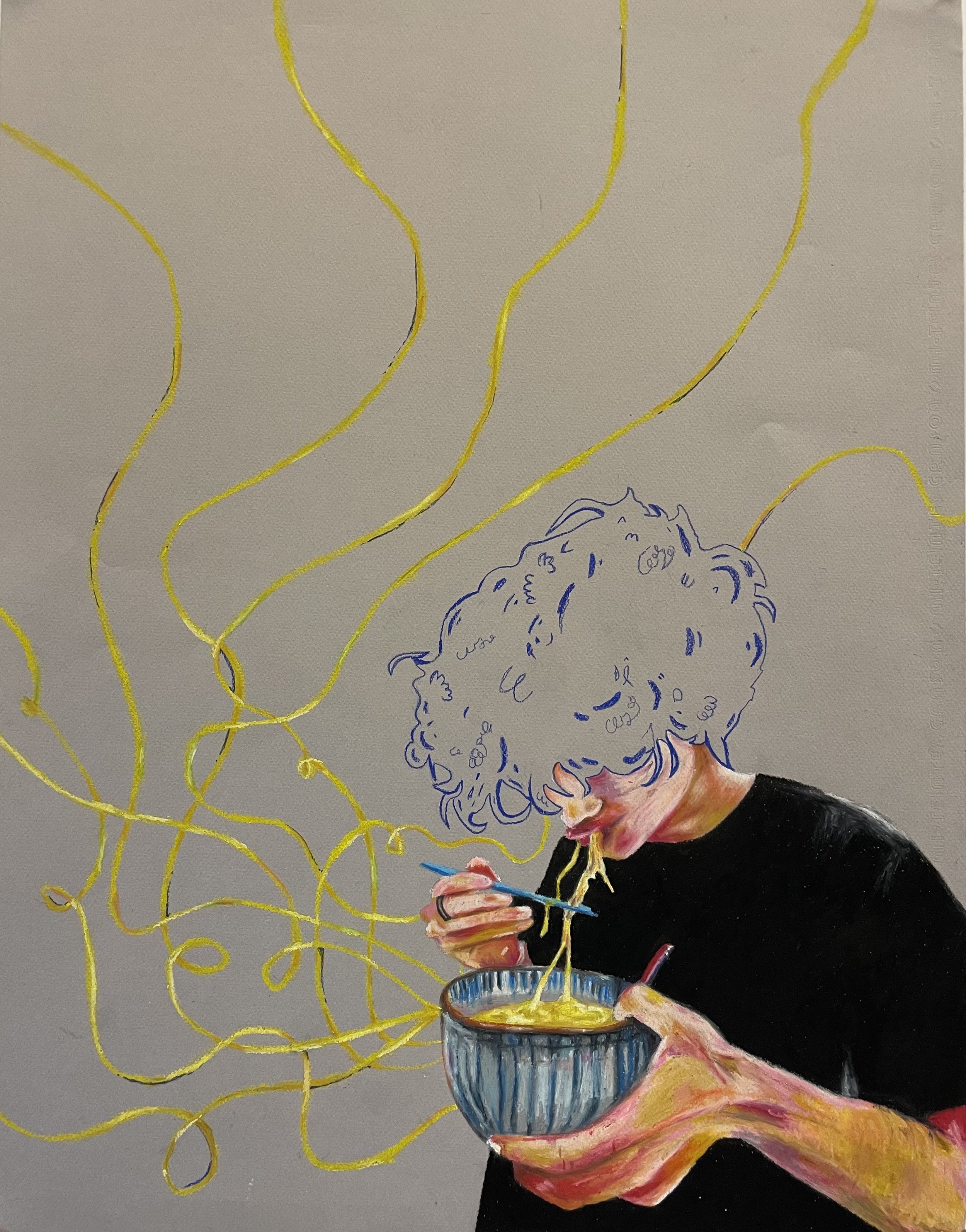

Miso, 2023

My first piece features a portrait of my brother. My brother and I were the first biracial people in our family, and we often discuss what this means, and how this separates us from the rest. Feeling caught between a place that does not wholeheartedly accept you, and an unfamiliar and distant culture is an experience many biracial children share. It is daunting when considered on a societal scale.

But keeping it within our family, neither of us speaks Tagalog, the first language of our grandparents. Often I have found that spoken words are not always the perfect form of communication. Nonetheless, my brother and I have still maintained an extremely close relationship with them. I believe this is because of my brother and my longing to eat and learn from them, to connect through chopping carrots, frying meat, and wrapping lumpia. Then again, by setting the table, passing around food, and sharing our creation. For many, food is a language, a way for people to connect on that deeper level.

As I grew older, I found that my stubborn grandpa’s way of showing his love was always cooking for us, and introducing us to dishes and to new ideas. In many ways, my grandpa’s cooking was an art; It was driven by emotion and inspired by his mood, but he never used recipes.

On a broader scale, food has been the way that my brother and I learn more about Asia as a whole since we have never been. My brother has nearly mastered the art of making ramen using miso and a series of sauces as his base. Much like my grandpa, this process has become an art, so, much like other art forms, a sense of tension is released while creating it, and equally so when consuming it. The bowl, spoon, and chopsticks also hold significant value to our family.

While he is consuming them, his head is emptied and all that is left is the sensation of warm broth running through his body. The source of the noodles, seeping out of the bowl, becomes undefined; I wanted to highlight the role food plays within him, and how an artist’s work can become entangled with their sense of self.

Throughout my life, food has always been so much more than just, nutrition, fuel, or a cure for boredom; it is the bridge between these two intangible places.

Love a Face Like Yours, 2023

This piece focuses on defining beauty as something inherent and lineal. If we can see beauty in the faces of people we love, it can help us to see beauty in ourselves. Our faces should not be compared to people in the media in an attempt to find value, but rather compared to the long line of people who have found love in each other.

Our traits are just a mosaic of the genes of our ancestors. They are a representation of a unique history, the embodiment of the rich emotions shared between people. This reframing is why I titled this piece, Love a Face Like Yours, which means the step that we have to take as individuals to ultimately appreciate ourselves and the worth we hold. Featured in this piece is my grandma, someone who I have always admired for both her beauty and her kindness. Although she is older now, there are still many pictures hung around her home of her dressed up in fur coats, linen dresses, voluminous hats, and retro sunglasses. Everyone always likes to admire them. Many of the portraits in this piece are based on one of these photos. I deliberately included a current portrait of my grandma as well to say that the beauty she held in those pictures has not wavered. Similar to my grandma, my mom is also someone who I have always admired for her beauty inside and out. Her brown hair, glowing skin, dark eyebrows, and smile are something that she and my grandma share. It was never hard for me to notice their beauty because of how much I looked up to them.

I outlined a figure in the back, who was captured by Hannah Reyes Morales. The woman is pregnant, and by not coloring her in I hoped to create a passage of time, as well as an overarching symbol of maternity within my piece.

Unfortunately, I often lost sight of my ideas of beauty as they pertained to my family. Within my school and within the media I consumed, there was a very narrow definition of beauty that rarely included brown hair, and never included a sense of intimacy. I began to separate my personal ideas of beauty from what I was being fed until my personal ideas didn’t even seem to fit the definition of beauty anymore.

From a very early age, I was reminded of the fact that some of my features made me different, which later came to mean that these features were what made me unattractive.

Tanned, 2023

My last piece in this collection, Tanned, is entirely based on a photograph from Hannah Reyes Morales’ 2020 collection: Redefining Beauty. This one, for me at least, almost completely focuses on complexion, melanin, and tanning as it relates to Filipino and Filipino-American beauty. I touched on this in all my pieces however, in this piece, it is significantly more prevalent as all the women are mid-tan.

To reiterate, in my collection, I created an overarching theme signified mainly by the vibrancy of the skin tones. I purposefully used varying hues of orange, pink, and yellow to accentuate their skin. For me, the shade of my skin has always been one of these features: a thing that stands out against people around me.

Conversely, it is seen as a sense of pride within my family. For a long time, I was the most tanned of my cousins, and for my grandpa, I was a staple of his home. Before I began school, my skin had always remained a blanket of familial approval because I knew that at home, there was comfort in likeness. It has taken me a significant amount of time to return to this mindset.

Growing up an Asian American in a predominantly white town and school, being tan often meant different things. For upper-middle-class white Americans, a tan could symbolize wealth: it always seemed to have a positive connotation. When my classmates would return after spring break, people always marveled at their trips to The Caribean Islands, Hawaii, and Mexico, and their complimentary tan complexions.

Although, I often times received this same kind of praise, when I was younger my tan represented something dirty, and something alien. During high school, I had people grab my arm as if I were a toy, captivated by my ability to tan.

When talking to my aunties and my Grandma’s girlfriends, they always said how beautiful I was and would compare me to various Filipino Pop stars and actors with lighter complexions, although I was flattered I knew this was only because I had Eurocentric features.

Within the Philippines, being tan is also a status symbol but in quite the opposite way. Being tan on the islands, according to my grandparents, was a sign of working long hours in the fields, which meant a lot of the time that they were from a more rural town. Hannah Reyes Morales also explores the concept of skin whitening treatments and how damaging that is to Filipinos. Given the Philippines' rich cultural history and ethnic backgrounds, it is backward and dangerous to define beauty as a singular thing. With so many groups living there, it is impossible for all of them to attain and fit into this one definition. By expanding the definition we can dismantle harmful practices and self-talk that only further the unhappiness we feel with ourselves.

Tying this all up, I wanted to return back to the idea of intimate and interpersonal beauty, as a alternative definition. The act of creating these pieces was a confrontation with beauty and worth within my art style. Using these materials and colors allowed me to not feed into my perfectionism. These pieces are by no means perfect, but they still are purposeful and important. This collection is not meant to critique so much as it is supposed to uplift those around me by mapping my personal history with beauty, complexion, and reflection. There is always a battle between our interpersonal and familial ideals and the ones imposed by society. It may not be possible to undo the damage that Filipino and American media has done, however, I urge people to redefine beauty within themselves, as something representative of people, communities, cultures, and worlds we love most.