The American Dream Instilled into the Filipino Household: An Oral History

Many Filipino Americans exude a sense of solidarity and loyalty to America, oftentimes even before immigrating. There were a series of factors that led America to have such a lasting impact on the islands. It seems that America was able to infiltrate almost all sectors both intimate and political. This created a group of individuals that, from the time of independence to the reign of Marcos, may not have had full access to the truth about political issues at the time. The political leaders of the post-colonial Philippines started to gain traction in the years leading up to Marcos’ rule, however, these tribulations fell on deaf ears in more rural parts of the islands. Some were unwilling to accept the negative effects of America, others did not even get the privilege of receiving such information. In the case of my grandpa, his Western ideals have always been present because of his father’s history with the U.S. military. Cut off from most major cities and flows of information, my grandpa depended on his father and his schooling to educate him on current events. However, in doing so, he developed a very pro-American mindset, one that embodied the American Dream. His life on the plantations new little discourse, only the need to provide for one’s family at any cost. During his final year of high school, his family was able to put funds together for him to access education in a major city: Manila. By the time my grandpa was 19, it was nearly his familial duty to find work in America in order to do the same, and financially aid his younger siblings. This was largely due to his father’s experience in Texas. His father always marveled at the benefits of America as an individual, but he never wanted his family to be there permanently, he only loved it because of what it offered his family back home. To this day, family will always come first for my grandpa. In the years leading up to the 1960s, many Filipinos, especially the working class, found that their loyalty resided with America because of America’s firm hold on Filipino politics, the military, and the public education system. America’s incentive was to keep the Philippines under its control even after they officially separated, which it enforced by painting itself in a more heroic light during a time when Filipinos were questioning America; In doing so, they unintentionally made America out to be a utopia, where Filipinos could allegedly access all the opportunities and economic benefits they had been deprived of.

America’s military presence in the Philippines acted as the bedrock for the integration of American ideals into Filipino homes. In 1898, America officially gained control over the Philippines. Previously, during Spanish colonial rule, Filipinos had little rights and occupied minimal jobs. They were fully suppressed under colonial rule so when America came with the proclaimed intentions of aiding the islands, they were in support. However, America did not view Filipinos as equals, but rather as people to indoctrinate with American ideals. Unlike the Spaniards, America implemented a “democracy”, although it did not function as democracy did in America. The ideals of democracy enticed many, even though this did not genuinely matter because the decision was not up to Filipinos. Once in control, America used this gilded image of itself to take advantage of many Filipino people and often used communities as pawns for American propaganda. During the WWII drafting, America extended its draft to Filipinos in exchange for dual citizenship and a taste of the promised land. Many Filipinos faced imbalances within the military, they did not get equal pay or benefits. However, loyalty to America was stronger than ever, as soldiers were often splitting their time between America and their own households. My grandpa recounts his father saying that as an American soldier, his title and position as such always came first, before the Philippines. His father glorified the West and his time in Texas. My grandpa speculates that this is because he was a humble and hardworking man who was not keen on complaining, especially when the results were bettering his family. In my grandpa’s home, there was not only a Western mindset but an understanding that America was their family’s main source of income, one way or another. As a family of nine, his father’s drafting and time in America were crucial, their only other source of income being his siblings’ part-time jobs. In this way, American loyalty crept into households and families across the islands until it became a widespread understanding.

American policymaking within the Philippines was often geared towards the financial benefit of America, sometimes these goals overlapped with the working or agricultural class of the Philippines, causing them to believe America was in favor of their betterment. For starters, the Filipino economy became highly reliant on their exports to America and other trade relations that America had set up. After the 1900s, the economy depended on agriculture within the islands. The Bell Trade Act allowed for a prosperous relationship between America and the Philippines. The act converted the peso into the dollar which in short, allowed trade to America from the Philippines to be free. America also promised to introduce new agricultural techniques, employed for efficiency. Unfortunately, these were underfunded and therefore not as useful as promised. However, the overall efficiency of production and harvesting was increased in the early 1900s. My grandpa was most certainly a beneficiary of this, and so was his community as he grew up in a place defined by their banana plantations. In bringing productivity and significance to agricultural workers, America gained the respect of many of the working-class communities.

Even after the islands were legally declared independent in 1946, America continued to occupy the islands, while also remaining present in cultures they had previously implemented. This is because of the slow fizzling out of American power, as they legally made all Filipinos into Aliens to the U.S. in 1934 with the Tydings-Mcduffie Act. Although this worked to benefit the Philippines’ path to independence, it also created more socio-political unrest. In labeling all Filipinos as Aliens to the U.S., the act created a legal distinction between these two identities, however, this only catered to American purity. Alongside this policy, America issued a transitional government called the Commonwealth. This was a 10-year plan set to help the islands transition into full autonomy. The fine print of this system was that every decision made by the Commonwealth had to be approved by America first, so the new system was not that different from the last. This consequence made it impossible for the Philippines to act freely because, without the consent of America, an action could not be made. This encouraged many rising Filipino political leaders to not only adopt American ways but to also prioritize America, especially economically, over their own country. This solidified America’s legacy, as the slow fizzling out of American power was not the clean break that was promised. The remnants would later not only influence political leaders but set the trajectory course for development.

America remained the dominant power within the islands until the Japanese invasion of 1941 when many Filipinos, if they hadn’t started to already, began to distrust dominant American ways. Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese invaded Filipino shores as well. However, at this time, the Commonwealth was still being controlled by the U.S. military. Given that America had been attacked just 10 hours earlier, the Commonwealth had little to do except stand idly by, waiting for orders. At this time, the formation of the Philipines as an independent entity was very weak and still in the works. Even excusing this fact, the Philippines was almost defenseless against Japan. By the time it had ended, the Commonwealth had barely even lifted an aircraft into the air. Most were shooting from the ground. After the damage had been assessed, many pointed fingers at America, in a blatant display of neglect. This became widespread proof for many that America did not have the people’s best interests in mind. There was an uptick in student protests and rebellion against the American way, which was especially prevalent in cities like Manila, Zamboanga, and Cebu. However, my grandpa had no recollection of these movements, even when attending his last year of high school in the city of Manila. This is where my grandpa’s story seems to deviate from the common one. He claims that the schools he attended never taught politics, they were mainly religious and language-based. In this way, my grandpa’s experience did not align with the denominate one, however, that is not to say that at this time, students weren’t rebelling and collectively questioning why American loyalty was being preached.

Public education, a system that America had established in the Philippines during their occupancy, remained heavily geared towards the West, which greatly influenced the new generation of Filipino people. Before America came, the Spaniards did not include Filipino people in their public education systems. With American colonialism, Filipinos were finally able to access public education, that was not just for elites. This was not a system that the people were eager to give up as America then left. However, not only did they keep it, but it remained unchanged. The main languages taught were still Spanish and English, excluding the native language, Tagalog. This is not to say that Filipinos were not working to rebuild Filipino solidarity and independence, but historically these efforts were put into predominantly cultural spheres, rather than economic, political, or educational systems. Throughout the 1930s the focus remained on this cultural sphere because many Filipinos felt they still had to prove to the world that they were not “savage” and that they were able to exist independently. The cultural aspects were also easier for activists and leaders to influence because many of the spheres were controlled by the Philippines’ Westernized government. For many children growing up in rural areas, the public school and their family was the only exposure they received to political issues. The news was often filtered through a pro-American lens, especially when it was not in the city.

Leading up to the 1960s, and Marcos’ election, the Filipino economy repressed job opportunities, making it difficult for low-income families to gain upward mobility. In the late 1950s, Espiritu claims that only a small percentage of graduating students were even able to be employed, and this was mainly college graduates. My grandpa stressed this, and why this ultimately led him to immigrate right out of high school, “If you are down, there is no going up in the Philippines.” For him, there was a mutual understanding that his only option was to travel to the U.S. His older brothers all had jobs and his younger siblings and parents needed support. He applied for a work visa almost immediately. He said that there was no future for him in the Philippines and his family urged him to move to the U.S. His father never wanted him to start a family here, he only wanted my grandpa to have a future and to benefit the family in the Philippines in a way that staying in the islands could not. He said that upon coming to the U.S. many of the immigrants on his boat had the same background, they were low-class children, looking for money to bring home to their families.

Many graduates’ only option seemed to be immigrating to America, in pursuit of the American Dream, for the betterment of themselves, but also their families. America’s everlasting presence in the Philippines showed how America intentionally played the good guy in the Filipino eye, but unintentionally advertised America as a haven for migrants. The West became this beacon of hope in the midst of a near-economic collapse and financial insecurity. In defining America as the savior, and thereby destroying Filipino autonomy, America could then create a world where the Philippines could not support its own people. This fueled one’s desire to seek opportunity across seas. Thereby, altering the defining factors of Filipino families and dynamics. Because this mindset had been indoctrinated into my grandpa, he chose to work in America and then eventually start a family there. To him there was no other option, it was inevitable.

Although my grandpa believes in American ideals and that this path was out of his own free will, his story corroborates one that suggests the influence of censorship, colonial powers, and propaganda. Upon coming to America, he states that it was a lot different than he pictured. He thought he would find work instantly, but most people told him he would not find one without attending college first. He also attests to the unwelcoming environment and political turmoil he became a part of. A lot of his stories uncover the unruly truth about immigrant opportunities and treatment in the U.S. He faced discrimination while working multiple jobs. He did not visit his family as often as his father did and his family rarely visited him. He worked jobs that uncovered the underbelly of corporate America. One was his job at Sealand, where he would receive shipments of dead bodies back from Vietnam, during the war. He said that many people around him often quit because of the various working environments. Even still, my grandpa does not regret his decision to come here because his idea of the American Dream centered around providing for one’s family, and since he was able to do that, he was happy. He never received the financial freedom that many middle-class Americans access today. However, most impressively, over the span of 20 years, he was able to pay for all of his siblings, except the eldest daughter, to come live with him in America, and eventually, he helped them get jobs and establish their families in the U.S. He has always known hard work, and is tough enough to withstand discrimination, so to him, this was the epitome of the American Dream: to work and to be rewarded, to be able to raise children in America, with access to the college education he never had.

Primary Sources

Bucoy, Freduardo. Oral Interview. Conducted by Audrey Green. November 22, 2023.

Orendain, Antonio E. II. “Zamboanga Hermosa.” Filipinas Foundation, Inc. 1984.

Secondary Sources

Goodman, Grant K. “The Japanese Occupation of the Philippines: Commonwealth Sustained.” Philippine Studies 36, no. 1 (1988): 98–104.

Jose Veloso Abueva, “Filipino Democracy and the American Legacy,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 428 (1976): 114–33.

Norman G. Owen, “Philippine Economic Development and American Policy: A Reappraisal,” In Compadre Colonialism: Studies in the Philippines under American Rule, edited by Norman G. Owen, 103–28. University of Michigan Press, 1971.

Resil B. Mojares, “The Formation of Filipino Nationality Under U.S. Colonial Rule,” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 34, no. 1 (2006): 11–32.

Rick Baldoz, “The Third Asiatic Invasion: Migration and Empire in Filipino America, 1898-1946,” NYU Press, (2011): 194-236.

Yen Le Espiritu, “Leaving Home: Filipino Migration/Return to the United States,” In Home Bound: Filipino American Lives across Cultures, Communities, and Countries, 23–45. University of California Press, 2003.

My Oil Pastel Collection: exploring interpersonal beauty & culture

This collection is a discussion of beauty and culture as it relates to my family. Art is often used as a commentary on society, a way to reflect on normalities that we have collectively created. However, for this specific collection, I chose to focus on the more personal side of some of these themes. I have found that viewing them in this light allowed me to see the more positive sides of things. These pieces were a reckoning of topics that I often push away, like otherness, belonging, and beauty as it relates to my Asian American identity. Throughout my process, as well, I questioned what I believed to be the idealized way of creating art. I ended up choosing oil pastels as my medium because they allowed me to be loose with both my linework and my shading. More importantly, this medium allowed me to be more forgiving as it cannot be erased and is difficult to cover up. I had to trust that my mistakes would not tarnish the beauty of the final piece, and only enhance it. In the end, my drawings imitated a kintsugi ceramic, with the imperfections making the piece more enticing.

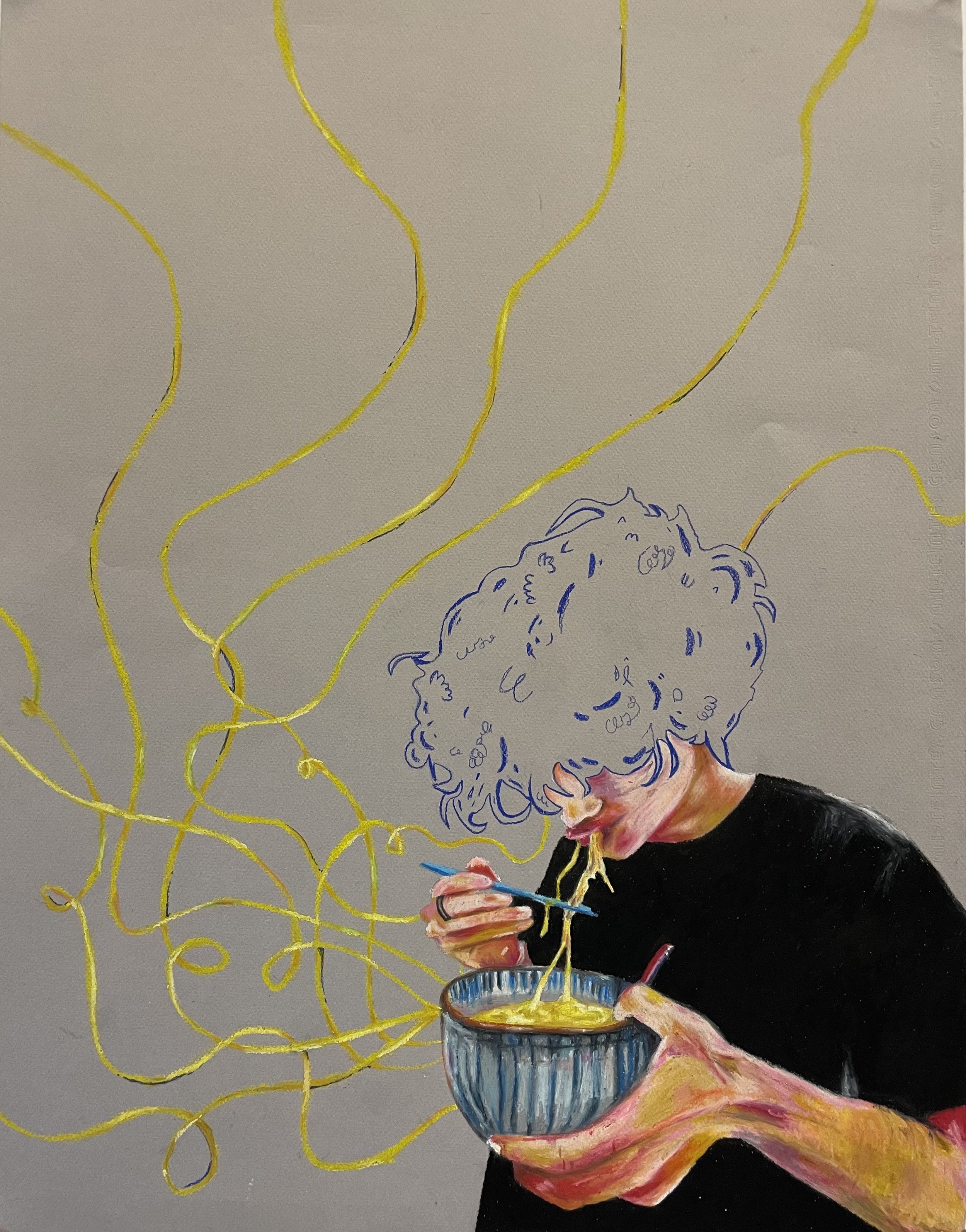

Miso, 2023

My first piece features a portrait of my brother. My brother and I were the first biracial people in our family, and we often discuss what this means, and how this separates us from the rest. Feeling caught between a place that does not wholeheartedly accept you, and an unfamiliar and distant culture is an experience many biracial children share. It is daunting when considered on a societal scale.

But keeping it within our family, neither of us speaks Tagalog, the first language of our grandparents. Often I have found that spoken words are not always the perfect form of communication. Nonetheless, my brother and I have still maintained an extremely close relationship with them. I believe this is because of my brother and my longing to eat and learn from them, to connect through chopping carrots, frying meat, and wrapping lumpia. Then again, by setting the table, passing around food, and sharing our creation. For many, food is a language, a way for people to connect on that deeper level.

As I grew older, I found that my stubborn grandpa’s way of showing his love was always cooking for us, and introducing us to dishes and to new ideas. In many ways, my grandpa’s cooking was an art; It was driven by emotion and inspired by his mood, but he never used recipes.

On a broader scale, food has been the way that my brother and I learn more about Asia as a whole since we have never been. My brother has nearly mastered the art of making ramen using miso and a series of sauces as his base. Much like my grandpa, this process has become an art, so, much like other art forms, a sense of tension is released while creating it, and equally so when consuming it. The bowl, spoon, and chopsticks also hold significant value to our family.

While he is consuming them, his head is emptied and all that is left is the sensation of warm broth running through his body. The source of the noodles, seeping out of the bowl, becomes undefined; I wanted to highlight the role food plays within him, and how an artist’s work can become entangled with their sense of self.

Throughout my life, food has always been so much more than just, nutrition, fuel, or a cure for boredom; it is the bridge between these two intangible places.

Love a Face Like Yours, 2023

This piece focuses on defining beauty as something inherent and lineal. If we can see beauty in the faces of people we love, it can help us to see beauty in ourselves. Our faces should not be compared to people in the media in an attempt to find value, but rather compared to the long line of people who have found love in each other.

Our traits are just a mosaic of the genes of our ancestors. They are a representation of a unique history, the embodiment of the rich emotions shared between people. This reframing is why I titled this piece, Love a Face Like Yours, which means the step that we have to take as individuals to ultimately appreciate ourselves and the worth we hold. Featured in this piece is my grandma, someone who I have always admired for both her beauty and her kindness. Although she is older now, there are still many pictures hung around her home of her dressed up in fur coats, linen dresses, voluminous hats, and retro sunglasses. Everyone always likes to admire them. Many of the portraits in this piece are based on one of these photos. I deliberately included a current portrait of my grandma as well to say that the beauty she held in those pictures has not wavered. Similar to my grandma, my mom is also someone who I have always admired for her beauty inside and out. Her brown hair, glowing skin, dark eyebrows, and smile are something that she and my grandma share. It was never hard for me to notice their beauty because of how much I looked up to them.

I outlined a figure in the back, who was captured by Hannah Reyes Morales. The woman is pregnant, and by not coloring her in I hoped to create a passage of time, as well as an overarching symbol of maternity within my piece.

Unfortunately, I often lost sight of my ideas of beauty as they pertained to my family. Within my school and within the media I consumed, there was a very narrow definition of beauty that rarely included brown hair, and never included a sense of intimacy. I began to separate my personal ideas of beauty from what I was being fed until my personal ideas didn’t even seem to fit the definition of beauty anymore.

From a very early age, I was reminded of the fact that some of my features made me different, which later came to mean that these features were what made me unattractive.

Tanned, 2023

My last piece in this collection, Tanned, is entirely based on a photograph from Hannah Reyes Morales’ 2020 collection: Redefining Beauty. This one, for me at least, almost completely focuses on complexion, melanin, and tanning as it relates to Filipino and Filipino-American beauty. I touched on this in all my pieces; however, in this piece, it is significantly more prevalent as all the women are mid-tan.

To reiterate, in my collection, I created an overarching theme signified mainly by the vibrancy of the skin tones. I purposefully used varying hues of orange, pink, and yellow to accentuate their skin. For me, the shade of my skin has always been one of these features: a thing that stands out against people around me.

Conversely, it is seen as a sense of pride within my family. For a long time, I was the most tanned of my cousins, and for my grandpa, I was a staple of his home. Before I began school, my skin had always remained a blanket of familial approval because I knew that at home, there was comfort in likeness. It has taken me a significant amount of time to return to this mindset.

Growing up an Asian American in a predominantly white town and school, being tan often meant different things. For upper-middle-class white Americans, a tan could symbolize wealth: it always seemed to have a positive connotation. When my classmates would return after spring break, people always marveled at their trips to the Caribbean Islands, Hawaii, and Mexico, and their complimentary tan complexions.

Although, I often times received this same kind of praise, when I was younger, my tan represented something dirty, and something alien. During high school, I had people grab my arm as if I were a toy, captivated by my ability to tan.

When talking to my aunties and my Grandma’s girlfriends, they always said how beautiful I was and would compare me to various Filipino Pop stars and actors with lighter complexions, although I was flattered I knew this was only because I had Eurocentric features.

Within the Philippines, being tan is also a status symbol but in quite the opposite way. Being tan on the islands, according to my grandparents, was a sign of working long hours in the fields, which meant a lot of the time that they were from a more rural town. Hannah Reyes Morales also explores the concept of skin whitening treatments and how damaging that is to Filipinos. Given the Philippines' rich cultural history and ethnic backgrounds, it is backward and dangerous to define beauty as a singular thing. With so many groups living there, it is impossible for all of them to attain and fit into this one definition. By expanding the definition we can dismantle harmful practices and self-talk that only further the unhappiness we feel with ourselves.

Tying this all up, I wanted to return back to the idea of intimate and interpersonal beauty as an alternative definition. The act of creating these pieces was a confrontation with beauty and worth within my art style. Using these materials and colors allowed me to not feed into my perfectionism. These pieces are by no means perfect, but they still are purposeful and important. This collection is not meant to critique so much as it is supposed to uplift those around me by mapping my personal history with beauty, complexion, and reflection. There is always a battle between our interpersonal and familial ideals and the ones imposed by society. It may not be possible to undo the damage that Filipino and American media have done, however, I urge people to redefine beauty within themselves, as something representative of people, communities, cultures, and worlds we love most.

Featured: Housing (In)Justice in The Bay Area

This is a featured article written by Andrés Martinez

The PROBLEM is RACIAL CAPITALISM!

Let it be known. From the beginning of the colonial states' conception, indentured servitude and enslaved people were in high demand globally. Those enslaved were mainly kidnapped indigenous people from different regions in continental America and Africa. They were not white. So, race shaped the national economic ventures by wealthy white men that were essential to the founding economic stability and longevity of what would soon become the United States. That market grew out of the extraction of labor from black and brown people and was defended by its perpetrators by all means. “Slave Codes” governing the mobility of Black people were in every state’s law codes and soon they’d be renamed to “Black Codes” doing quite exactly the same: establishing institutional governing of black people to easily silence when they see fit. Racialized capitalism in the U.S. requires this kind of policing so that Black Americans are unable to infringe on the assured power of majority white elites. Initially, when it came to housing, racial capitalism was bound up in white supremacy through redlining and other forms of exclusionary zoning and displacement. Even as these practices become somewhat socially unacceptable and somewhat legally prohibited, our society continues to exist in racial capitalism. As contemporary narratives of the Bay Area portray it as progressively inclined, the structures in it have not transcended racialized forms of housing discrimination. The legacies of exclusionary zoning laws continue to shape current housing policy. Urbanization disproportionally displaces low-income to no-income people of color. The institutions within RACIAL CAPITALISM continue to refuse public affordable housing to be considered a

HUMAN RIGHT.

The issues. Not at all an exhaustive list of the intersections of economic/social class, race, gender, and sexuality that make it so housing in the Bay Area is either more or less accessible to an individual.

Gentrification. Capitalist urbanization historically disproportionally displaces communities of color.

It is often regarded as urbanization under a single motivator, money. This is only part of a fuller truth. In opposition to NIMBY politics, an ideology that established itself as political action based on the needs of predominantly white neighborhoods, YIMBY took shape. Opposite to “Not In My Back Yard” politics, “Yes, In My Backyard” politics promotes up-zoning and development to combat urban segregation. A fault in this is that this thinking forgets the history of displacement from urbanization and these changes in communities of color result in evictions due to increased housing prices. Likewise, transportation development is another form of gentrification that has put low-income renters at risk for eviction. Often well-funded transportation developments may connect neighbors to a larger economy with more opportunities for class mobility. What if a person is already employed in their neighborhood? Then, these kinds of developments might drive them out as housing demand increases, hence rent prices as well. Under a false notion of equity, policymakers fund public transportation developments in low-income neighborhoods to attract higher-earning people into an area already settled in. Neighborhoods are entirely disrupted, and people are evicted and unhoused.

Devaluation of Black-owned assets.

Land and home ownership is inextricably linked with power and generational wealth in the United States. The wealthy are able to afford to own more than one home to build their wealth and predominantly low-income people of color can not. Even as laws that had kept black homeownership, especially in white neighborhoods, at a low, the value of their assets today is still linked with perceptions of Black people. ALL over the United States, Black-owned property is disproportionally devalued. In San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward, there is a -27.1% average devaluation of homes in majority Black neighborhoods. In the United States, this racial bias amounts to $156 billion in cumulative losses for mainly Black individuals and families.

Criminalization of homelessness.

Criminalizing homeless people will never solve homelessness. Homeless people often reside in neighborhoods that are already disproportionately policed and are then likelier to receive violations for committing “uncivil” behavior otherwise allowed if done on private property. They have no other choice but to do so. These are anti-homeless policies that ban sleeping, panhandling, and camping which is all necessary if someone is unhoused and with little to no income in the Bay Area. Those who receive citations for this are more likely to be incarcerated because of a prior conviction and given high bail amounts. Even when interactions with the police are non-violent and non-confrontational, there is rarely information on affordable housing and other resources shared. Criminalizing and policing homeless people will never solve homelessness.

Solutions in the NOW. Again, not an exhaustive list. Changing and dismantling the institutions of the present require not one solution to make housing equitably accessible to everyone in the Bay Area. The following solutions are mostly working within the systems of oppression in consideration of the issue at present, but ultimate housing equality will be achieved outside of any capitalistic society. True housing equality will be only found in a large dismantling of how the U.S. functions in reckoning with its legacies of racialized violence and exclusion.

Anti-displacement solutions to homeless people and prevent further homelessness.

Increase the required number of affordable housing in all new housing developments in all counties.

Formalize a more standard practice in how the value of homes is assessed. No possibility of racial bias.

New public housing programs that are healthy, energy efficient, and affordable housing. Energy-efficient housing is less likely to have mold and other toxins which leads to healthier lives.

Place new public housing in “high-opportunity” locations because it is so rarely done so. Also, housing programs must offer high-quality free career services.

Adopt Fair Chance Ordinances into local legislation. In Richmond, City Council voted “Fair Chance Access to Affordable Housing Ordinance” into local legislation. It makes it possible for people with prior arrest and conviction records to be considered for housing that they would not have been considered for otherwise. Housing providers are able to acquire an applicant's criminal record but are only allowed to review it after offering housing.

Overturn anti-homeless laws now. Legislative policing of the movements and actions of homeless people who are predominately people of color in the Bay Area can be changed and ruled out altogether. This change can be made on all levels of government.

Bibliography

Herring, Chris, et al. “Criminalization Fails to End Homelessness in San Francisco.” Housing Matters, 29 July 2020, housingmatters.urban.org/research-summary/criminalization-fails-end-homelessness-san-francisco.

McElroy, Erin, and Andrew Szeto. “The Racial Contours of YIMBY/NIMBY Bay Area Gentrification.” Berkeley Planning Journal, vol. 29, no. 1, Mar. 2018, https://doi.org/10.5070/bp329138432.

Menendian, Stephen. “Transportation Policy Is Housing Policy.” The Berkeley Blog, 6 Sept. 2013, blogs.berkeley.edu/2013/09/06/transportation-policy-is-housing-policy/.

National Housing Law Project. Fair Chance Ordinances: An Advocates Toolkit. www.nhlp.org/wp-content/uploads/021320_NHLP_FairChance_Final.pdf. Accessed 9 Nov. 2022.

Palm, Matthew, and Deb Niemeier. “Achieving Regional Housing Planning Objectives: Directing Affordable Housing to Jobs-Rich Neighborhoods in the San Francisco Bay Area.” Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 83, no. 4, Oct. 2017, pp. 377–88. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2017.1368410.

Perry, Andre M., et al. “The Devaluation of Assets in Black Neighborhoods.” Brookings, Brookings, 27 Nov. 2018, www.brookings.edu/research/devaluation-of-assets-in-black-neighborhoods/.

“Plan, Issues, Housing.” Racial Equity Tools, www.racialequitytools.org/resources/Plan/Issues/Housing. Accessed 9 Nov. 2022.

Schten, Rachel, et al. California’s Low-Income Weatherization Multi- Family Program Successes, Challenges, and Implications for Housing Justice. www.urbandisplacement.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/LIWP.pdf. Accessed 14 Nov. 2022.

UC Berkely Social Science Matrix. “Homelessness and the Bay Area Housing Crisis.” Social Science Matrix, 28 Sept. 2020, matrix.berkeley.edu/research-article/video-homelessness-and-bay-area-housing-crisis/.

The Belittelment of the Perspectives from Women of Color in Abstract Expressionism: A Manifesto

The world of art has seemed to have stayed subjective. Unlike politics and science, one cannot deem something right or wrong, so the success of artists and artworks relies largely on their beauty and impact on other people.

In the late 1800s, the impressionism movement started in France with artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas. During the 1900s, Post World War II, the art world decided to move away from realistic and visually accurate pieces, making way for the abstract expressionism movement in New York and the stylized works of men like Jackson Pollock. What these two movements had in common is their focus on the artist as an individual, as the art was more representative of the world through the artist’s eyes. These movements worked to bend the standards of art as well as their intended impact. Suddenly, art was not just about skill and replication but also interpretation and imagination, showing the world as it could be, should be, or just how the artist saw it. (Personally, my own art is heavily influenced by my experiences and my emotions, so without these movements, my art would not be recognized as such.) And although this proved beneficial for many artists and their freedom of expression, this also opened the door for people’s implicit bias and racist tendencies to factor in.

Many women, but especially women of color, fell short of success in the art world because of the inescapable fact that their voices would not be valued as much as a white man’s would be. The works became meaningless simply because the majority could not relate to them. The significant misrepresentation of the women of color that defined this movement only proves that we have to re-examine our perceptions of good art and art that relies largely on storytelling. However, this extends further than the art world. It is a constant struggle for women of color to have their experiences recognized, let alone prioritized. Within the art world, we have been quick to label honoring women of color artists for their techniques as progression, but many still fail to notice these women in the same way when their art is not so linear or universally understood. So learning to empathize with abstract ideas and art is a skill that will become applicable to many other branches of representation, not just the abstract art world.

Societal impacts aside, abstract art and other forms of self-expression have been a vital part of coping for many women of color. It is crucial to first understand why the stories told through art, by women of color, in particular, are profoundly meaningful. Historically, marginalized voices have found ways to represent themselves in less “threatening” and apparent ways. Methods such as fiction literature, music, and poetry have seemed to be defined differently for these marginalized voices. This is because, as a marginalized voice, it is hard to even have your ideas leave the confinements of your own mind. Audre Lorde, a Black poet, in describing her own desire to write, stated: “It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are- until the poem- nameless and formless, about to be birthed, but already felt.” She highlights that there is something beautiful and enlightening about a narrative derived from a suppressed emotion. Lorde defines her light as poetry, something that is a vital aspect of her being, not just a “luxary.” This distinction shows how the perspectives shown through her poetry are necessary to rationalize emotions and inflict change. I believe the way she talks about poetry can also be applied to more general forms of art. Forms of self-expression are like languages in that they convey essential ideas that would otherwise be formless. Even within Lorde’s own path, she repeatedly spoke out during the 1980s about the lack of recognition for women of color within the broader feminism movement.

Throughout history, the emotions of women of color have been labeled as impractical and unserious, so within a movement so devoted to loose figures and colorful swirls, this argument should become invalid. However, we have chosen to deny ourselves of comprehending these select narratives. Only leading us to a place where the true meaning of abstractionism and expressionism are almost exclusively applicable to the works of white men alone.

“The motive behind the Black aesthetic is the destruction of the white thing, the destruction of white ideas, and white ways of looking at the world. The new aesthetic is mostly predicated on an Ethics, which asks the question: whose vision of the world is finally more meaningful, ours or the white oppressors’? What is truth? Or more precisely, whose truth shall we express, that of the oppressed or of the oppressors?”

Similarly, within The Black Power Movement, there was a movement that focused solely on the intersection of politics and art: The Black Aesthetics Movement. Although this movement centered around poets in particular, their broader goals were again relevant to many artists’ path to distinction. In 1968, Larry Neal, a member of the Black Arts Theater, wrote, “The motive behind the Black aesthetic is the destruction of the white thing, the destruction of white ideas, and white ways of looking at the world. The new aesthetic is mostly predicated on an Ethics, which asks the question: whose vision of the world is finally more meaningful, ours or the white oppressors’? What is truth? Or more precisely, whose truth shall we express, that of the oppressed or of the oppressors?” This essential question is what we should all be asking ourselves when looking at works that so heavily rely on the experiences of the artist. Redefining what meaningful art is would call on people to deconstruct the biases that may influence the way they view beauty. Unlike the White artists in the 1950s, artists within BAM centered a lot of their works around the manifestation of progression and liberation. However, when Neal refers to the deconstruction of white ways of looking at the world, I do not think he is only referring to political art. More so, the perspectives of African-Americans holistically.

Artists of color were commonly thought of as apprentices or hobbyists, not defining members of the expressionism movement. Alma Thomas, an active member of the abstract expressionism movement, remains one of the few women of color credited with this role. As art institutions begin to recognize the art of women, they are still highlighting predominantly white women. Alma Thomas is also known for her role as a tenacious art teacher within her community. However, her art pieces themselves were not as well known as expressionism until after her death.

The most attainable goal for these artists would be recognition and representation for their contribution to the movements. Adding their names to the websites, museums, and textbooks would not only give them the credit they deserve but would represent these movements more truthfully. However, the measures needed to prevent this same outcome in the future are much more rigorous. First, people who view art would need to dismantle their biases towards beauty and worth. Within a profession so dependent on preference, it is important that people understand how these biases would influence their perception of the works. We usually attach meaning to abstraction when we see or feel something familiar. Without this connection, a piece can look like a bunch of miscellaneous shapes and colors. However, expressionism is not about an unfamiliar viewer. For the artist, they have exhausted meaning, often pouring raw emotions into their work. So, just because the people defining the piece’s worth do not understand it, another group of people likely will. But more importantly, the artist’s ability to put feelings into lines, freely creating their own techniques, is already literally what the abstract expressionism movement was about. Defining success as it relates to a handful of art institutions would change the meaning of the said movement. That does not mean that people have to buy art that they do not like, it just means that these artists should be given a platform by prevalent members of the art and art history communities, uplifted for the people who will understand them. Once this can be done, adding more women of color to boards of museums and as gallerists would allow the “stamp of approval” to be given by more than one perspective. Having diversity within higher levels of the art world will make art as a profession more accessible and make success more attainable for women of color.

The most important step however, is teaching people who are offered countless forms of representation to empathize with marginalized stories. I know it is possible because any person of color can tell you that they have been doing it their whole lives. One of the reasons why people are so quick to dismiss the meaning of a piece is because they are not willing to think on it and learn from it. A modern example of this would be the extreme backlash Pixar’s “Turning Red” received before the movie even came out. The movie was about a Chinese-Canadian girl growing up in the early 2000s and going through puberty. Critics and random YouTubers alike claimed that the character and her struggle were too specific. After the movie came out, many of these same people said they disliked the movie because it wasn’t relatable. Sean O’Connell, the managing director of CinemaBlends, tweeted, “Some Pixar films are made for universal audiences. ‘Turning Red’ is not. The target audience for this one feels very specific and very narrow. If you are in it, this might work very well for you. I am not in it. This was exhausting.” Growing up as a woman of color, I quickly learned to appreciate and enjoy Pixar and Disney movies that did not depict my life. However, there seems to be an underlying theme in the criticisms of modern representational movies: the movies aren’t relatable for the critics anymore, thereby making the movie a flop. Yes, this plot line is very particular, and so is the plot line of that one movie about a cooking rat in Paris.

This clearly connects to expressionism, as people who have not been under-represented do not have the skill of empathizing with others and understanding an emotion that is not their own. When people in the art world, similar to O’Connell, view something that they relate to, it becomes “universally” acclaimed. Contrarily, when a woman of color’s perspective is shown to a group of white men, hardly qualified to speak on it, it is dismissed. Everyone can work to develop the skill of empathy for the sake of self-expression and art professions. It would also help most people better understand the feelings, intentions, and aspirations of communities. Having empathy, whether viewing an animation about a Chinese-Canadian girl or a bold stroked, and colorful painting of a flower, will always lead one to have a greater appreciation and understanding of the perspectives of others.

“Alma Thomas: Your New Favorite Artist.” Alma thomas: Your new favorite artist. National Gallery of Art. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.nga.gov/audio-video/video/ynfa-alma-thomas.html .Gotthardt, Alexxa. “11 Female Abstract Expressionists You Should Know, from Joan Mitchell to Alma Thomas.” Artsy, June 29, 2016. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-11-female-abstract-expressionists-who-are-not-helen-frankenthaler .Lorde, Audre. “Sister Outsider.” 1984. Lorde, Audre. “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism.” Women’s Studies Assosiation Conference, 1981. Neal, Larry. “The Black Arts Movement Drama Review.” 1968.Tong, Quynh Anh. “A ‘Turning Red’ Review: Is There a Bad Way to Do Representation?” The State News, March 31, 2022. https://statenews.com/article/2022/03/turning-red-review?ct=content_open&cv=cbox_latest#:~:text=People%20criticized%20the%20movie%20for,amount%20of%20the%20population%20experiences. “'Turning Red' Cast Speaks up after Controversial Review Was Called 'Racist' and Pulled Offline.” Yahoo! Sports. Yahoo! Accessed November 8, 2022. https://sports.yahoo.com/turning-red-cast-speaks-controversial-223826038.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAGL3-QKO8Unxx7ZxaVedwmxRGjxssDj1F4dr-2LhchThKuGpK9ukZbWQDKLbuXA9VsHn03Avb2x9t2zAl8UFU4pwAlQUg5vjHBm2Olx3rrm1yWzH3EHX9HdanfsaFYhqB9UN-GIN1c4ZsgDNxdv1UnbK-KAvLW1YHxyEnO2C5HX5 . Baníg & Manggá

My mother told me that when she walked into this gallery, tears were brought to her eyes for one reason: she said she had never seen such a common household item displayed on the walls of a gallery in such a beautiful way.

Courtesy Silverlens New York, 2022

Silverlens’ gallery on Martha Atienza and Yee I-Lann’s work features a number of projects. These include a series of woven mats or baníg, videography on the waters of the Bantayan Islands, and a series of black and white photos telling the story of Yee I-Lann’s relationship with Southeast Asia’s various administrations. Martha Atienza is a Dutch-Filipino woman living in The Bantayan Islands, while Yee I-Lann is from Sabah, Malaysia. My mother and I were lucky enough to have the gallery further explained to us by Silverlens’ director, Katey Acquaro. She took us through the gallery and explained the significance of the mats as well as the images that they displayed.

The mats were intended to tell a story of the power language had on culture and family values. As we all know, the Philippines were colonized by the Spaniards. With that, many changes occurred economically, politically, and culturally. Filipino people were forced to adopt new gastronomy, a new religion, and of course, a new language. Their art works to highlights the impact of language on families within a community.

Courtesy Silverlens New York, 2022

Baníg was a very common household item, used for eating and sleeping, among other things. However, when the Spaniards came and tables were introduced, Filipinos were forced to bring this new language inside their own homes, a place of sanctuary, as there was no word in Tagalog for “table.” Suddenly, there was no sense of resistance or separation, and the inevitably of Spanish influence became reality. The table, a symbol of colonial rule, is raised off the ground, unlike the mat creating a symbolic hierarchy of cultures; she viewed this distinction as menacing. In Malaysia, she felt a part of her language, more so culture, was lost to colonialization, which is a feeling and issue many Southeast Asian families have. My mom and I remember my grandparents’ hoard-ish nature toward these mats. They were found scattered around, on top of tables, in cabinets, and hidden in between the fridge and the oven. But in this gallery, they were lit and decorative in an illustrious sense. For the first time, I saw these mats not in an inferior or useless way but for what it truly was, an art. Her mats act as a progression of this dissociation, showing the table depicted on the mat fade into abstraction. Devastatingly showing how traditional words and customs were neglected in the face of influence. For me, it showed the forcefulness of change inflicted on Filipinos within a place of intimate continuation. Everything around them became distant and unfamiliar, even within their own home. We often view colonization through a governmental lens; however, her art argues that the interpersonal and personal impacts were far greater.

However, Yee I-Lann’s photo essay touches more on the political sides of colonization. In her photos, she has people in various poses on or with mats, some containing other props such as office chairs and desks. These photos focus on how these objects conflict and coexist in the same space of the photo. She uses furniture as a metaphor for power dynamics. Similarly, she will contrast men in suits with women in traditional clothing and accessories so that the viewer can grasp the divide and tension between these two beings.

Courtesy Silverlens New York, 2022

“Mom rarely spoke Tagalog. She called it useless. In Fort Myers, a town of retirees and fishermen in Robert E. Lee County, Florida, it was. Mom had moved here to escape the poverty of the Manila slum where she grew up. She’d left her islands to become an island, a speck of brown adrift in a sea of the white and elderly.”

My Favorite photo of this series is one that centers around a mango tree against the backdrop of a dark cement wall. When I saw this photograph in the context of her other works, I instantly thought of a story I read about the importance of a mango tree to a Filipino immigrant family. The story, The Mango Missile Crisis, written by Annabelle Tometich, recounts the day that her mother, an immigrant from the Philippines, was arrested for shooting a man with a BB gun after she had watched him steal mangoes from her tree. The author’s intent was to help people empathize with her mother and to further explain the hardships that had led her mother to this moment. Tometich writes, “Mom rarely spoke Tagalog. She called it useless. In Fort Myers, a town of retirees and fishermen in Robert E. Lee County, Florida, it was. Mom had moved here to escape the poverty of the Manila slum where she grew up. She’d left her islands to become an island, a speck of brown adrift in a sea of the white and elderly.” Her mother felt like the other, isolated in a culture that she did not understand and that did not accept her. Someone who viewed this arrest with emotions aside, would question the significance of a mango tree, and why someone would be so compelled as to risk their freedom for it. After reading this story, it was clear.

Her mango tree was not just a plant adorning her backyard, it was a reminder of home. It was a beacon of familiarity in a sea of the unrecognizable. Similar to Yee I-Lann’s mats. Tometich realized that to her, this act of anger was almost justified. She regretted her reluctance to understand her mother, as she knows now that this hesitance only worsened things, “I want to go back to that thirteen-year-old dodging the projectiles, if only to tell her things will get better. I want to hug her the way her mother rarely did. I want her to be a kid and wish for kid things: world peace, ponies, love notes from crushes. Or maybe just a lightweight jean jacket suited to winters in Florida.” Going back to the photograph, this vine from a mango tree reminded me of Annabelle Tometich’s mother, pinned against a cement wall: the solidity of American culture.

This gallery successfully invoked many emotions within my mother. Growing up in an unfamiliar place where society is constantly telling you that your methods and treasures are useless, it is important to push back in order to preserve tradition, but also a sense of gratitude. We realized that we do not have to deem something beneath us just because the people around us do not see it in the same way. Whether it be a mat or a mango tree, it is important for the Asian-American community to hold memories of their past with them. By learning more about the significance of these memories, it will become easier to connect and appreciate someone else’s history and why they may feel the way that they do about change.

Photos courtesy Silverlens New York, 2022

Tometich, Annabelle. “The Mango Missile Crisis: Annabelle Tometich.” Catapult. November 23, 2021.

The Problem With Shang-Chi: Racism, Stereotypes, and Kung Fu

Although Hollywood has somewhat distanced itself from the perpetuation of Asian stereotypes such as the background comedy relief or the exotic Asian woman, it evidently still has quite a ways to go. Some of these modern-day stereotypes are harder to recognize as they are masked by a character's otherwise heroic, or desirable qualities. I believe Hollywood’s struggle comes from its audience, many times I feel like the movies I watch about my culture are not written for me but about me. However, this difference is significant as it oftentimes leads to a false sense of representation, especially for young and impressionable audiences. To be truly represented in film means to see aspects of your personal way of life, it is not seeing an unrecognizable and exterior perception of your culture projected onto the big screen, no matter how positive the light.

Shang-Chi exudes a stereotype best described by Charles Yu in Interior Chinatown as “Kung Fu Guy.” “Kung Fu Guy” embodies not only the admirable and powerful traits aspiring actors seek but also the highest achievement one can possibly reach as an Asian in the industry. Yu’s satirical screenplay pokes at Asian stereotypes that seem to have Asian actors in a stiffening chokehold. His character, Willis Wu only ever aspired to play one role, a Kung Fu master. He describes the feeling of seeing this role for the very first time and wondering, “Who is that, that is not just some Generic Asian Man, that is a star, maybe not a real, regular star, let’s not get crazy, we are talking about Chinatown here, maybe A Very Special Guest Star, which for your people is the ceiling, is the terminal, ultimate, exalted position for any Asian working in this world, the thing every Oriental Male dreams of when he is in the background, trying to blend in. Kung Fu Guy.” After years of derogatory roles which portrayed Asian people as uneducated and somewhat inhuman, there was finally a persona that didn’t seem so bad; In fact, he was more than good, he was strong, brave and most importantly he was not cast aside, hidden under the shadows of another. Bruce Lee, to me, is the most notable “Kung Fu Guy.” He decorated the 1970s with his martial arts movies and set a new standard for Asian Men in film.

So what is the problem with all this? After this new portrayal of a not weak, but strong Asian man was widely accepted it was then exhausted. There were not many other movies at the time that featured different personas other than the one Kung Fu Guy. After reading Interior Chinatown, I felt like Marvel’s 2021 movie was taking me back in time.

The settings only added to the outdated-ness of “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings.” Marvel not only cast Simu Liu as an obsolete character but also depicted his “homeland” as this never-advancing world, unlike the West. This furthers the space between Shang-Chi’s two identities as if it were a legitimate fictional universe. When they finally return back to New York every aspect of his “cultural journey” remains in this fantasy land.

Evidently, Interior Chinatown concludes when Willis Wu decides to break free from the stereotypes that came with his profession to just be a dad. He first becomes immersed in the anger of continuously not fitting into any of the available roles. As a result, he literally begins to break down the walls of the racist institution that wronged him. His character is a mere symbol of countless Asian males’ relationships with media like this film.

Hollywood taught us that this was “the ceiling” and that what young actors should aim to do is fill the hollowness of the uncast stereotypes written by Hollywood itself. What audiences always seem to forget is someone doesn’t have to have an unbearably inaccurate accent to be a movie stereotype. Portraying this role as if it is the epitome of “Asianess” is to say that we will never transcend our characters, not just on the screen, but in the greater scope of the world. Marvel could have done a better job of developing the originality of Shang-Chi as a character so that he resembled the audience more than the Asian male in previously profitable films. Validating a stereotype demotes the ideals of individualism, authentication, and separation that we need to be reminded to work against. Limited choices limit what one can imagine for himself. It is not to say that dreaming of playing a kung fu master is bad, but that it is okay to dream of even more.

A Photo Journal: Lolo & Lola’s Garden

The Secret Garden

My brother and I wanted to recreate what this garden looked like to two young grandchildren. To us, this concrete backyard, that neighbors the backend of a restaurant kitchen, was magical, mysterious, and green.

This house has always been a symbol of my family’s bay area roots. When I was born, this house belonged to my grandparents, and now it belongs to my cousins. Nevertheless, chips and imperfections have continued to decorate this house over the course of time; making it even more special and beautiful to the many people that have shared memories here. We attempted to capture the essence of a very specific part of the house through a series of photographs: the backyard.

This tub was the home of my first pet. Hidden under the second floor of the house, the koi pond sat on a floor of hand-placed bricks. All nine koi fish had a special name that was significant to my grandpa. My grandpa had named mine Princess. She was white and embroidered with vibrant orange spots. My cousins and I spent San Fransisco summer days sitting on the stones surrounding the fish tub, feeding the fish with fish food we had found in the back of a shed.

Buwan ng Kalutong Pilipino

In 2018, the month of April became The Philippines' national food month. This month is dedicated to the generational traditions and practices that surround agriculture and food. The government’s intention was for families to have time to celebrate their culinary heritage during this special time each year. Additionally, people hope it will uplift the islands' food tourism as well as Filipino-American restaurants.

In honor of National Food Month, I wanted to share my relationship with Filipino cuisine and what this celebration looks like for me. Over this past month, I visited my favorite Filipino restaurant in San Fransisco, as well as a new restaurant in Los Angeles. I also re-made some of my favorite traditional and current recipes. Every Filipino could celebrate this month differently as food and agriculture play different roles in every family. As someone whose grandparents come from practically opposite sides of the islands, the dishes that we cook in our family vary in style. “Filipino style food” looks different across regions and that is why I love trying new restaurants and recipes to celebrate the month of April. This is a way for me to learn about new Filipino cuisines and what they may have been influenced by.

My favorite restaurant right now happens to be Senor Sisig, in the Bay Area, whose food is a great example of this. Their “street food” style centers around pork and vinegar flavors. They are infamous for their burritos and tacos, while they also have rice or nacho bowls. I would describe their flavors as Mexican-Filipino fusion. My favorite menu items are tosilog and the “senor” sisig burrito. If you are looking for something more reflective of Filipino cuisine then order the tosilog burrito, as it is filled with adobo rice, tomatoes, and of course, a fried egg. If you plan to dine here, do not forget to ask for a side of their pepper and chili vinegar dipping sauce.

Next, I found myself at Sari Sari Store in Los Angeles’ Grand Central Market. While this restaurant also happens to center around “Filipino street food” its menu looks very different from Senor Sisig. Their dishes are mostly rice bowls and smaller snacks or sweets. When we went, we ordered four rice bowls and lumpia. These rice bowls were the BBQ pork belly, adobo fried rice, lechon kawali, and lechon Manok. All the meat was cooked to perfection and was the ultimate blend of salt and sweetness. My mom loved how every rice bowl had a crispy fried egg with a runny yolk on top. The rice bowls encapsulate a lot of the same flavors that my family and I use, so they were a 10/10. However, my first bite of my lumpia surprised me. The meat was cooked and seasoned in a way that I had never tried before. The meat was soft and flavored heavily with ginger and scallions. Although I did like this, it was unlike any lumpia I had made or bought before. What tied this meal all together was their signature vinegar sauce that seemed to contain fish sauce, black pepper, ginger, garlic, and chilis. The vibe of the restaurant was extremely nostalgic as the bar was adorned with many of The Philippines’ most iconic flavors. The shelves of the bar were lined with, sriracha, fish sauce, Jufran, and condensed milk. The bar also circled the little kitchen in the middle where you could see all your food being made. I definitely recommend trying one of these restaurants before the month is over. If you don’t live near these restaurants or you are looking for something new, do some research on Filipino-owned restaurants and vendors in your area. If you do not feel like leaving the house at all watch out for our next article that will contain my favorite modified and traditional recipes that are easy to make at home.

Growing Filipino-Owned Online Businesses

Supporting small businesses allows us to shop for items that are often left out of popular culture. Some of the most unique clothes, accessories, and decor I own are from small, local businesses. Shopping at these stores is also a way to uplift our communities and reduce our carbon footprint.

Recently, I have found some unique, Filipino-owned small businesses that are worth your money. Not only is it essential to support these businesses because they are growing, but also because they work to maintain a cultural presence in mainstream media. Here are only a few of my favorite Filipino-owned shops that you can support through their websites:

First is Shop Para Sa’Yo. Two Filipina-American sisters created a curated selection of Filipino-inspired gifts, packaging, boxes, and much more. Personally, their gift selection is very nostalgic and incorporates a lot of meaningful items that I associate with my childhood and Lolo and Lola’s house. One of my favorite gifts is the Spam candle; this is a papaya and mango scented candle made from soy. My other favorite is the Filipino sewing kit pin, which is in fact, a blue cookie tin. These gifts have personalized messages or a gift tag that will be handwritten upon ordering.

Next is the apparel shop Bahala Na based in Los Angeles. They feature minimalist and cute hoodies and shirts that are embroidered with the shop’s easy-going name: “Bahala Na” meaning “come what may.” This is a saying that has significance to the brand and its values. My favorite shirt is their “Bahala Ka Sa Buhay Mo Tee” in white. I just found their totes that have Bahala Na printed in red lettering, and I will definitely be purchasing one in the weeks to come.

Lastly is Emme Essentials; although they are not exclusively a Filipino brand, I still wanted to include them because they feature Filipino scented candles. This Asian-American couple’s mission was to create an assortment of Asian-inspired candle scents ranging from lychee to pomelo. The couple wanted to create a smell of comfort to those missing home, as well as a way to connect their culture to different people. My favorite is the ube scented candle which takes on a slightly woody, vanilla aroma that is accurate to the name.

The Filipino Plate

Filipino cuisine is derived from our rich history and compiled from its diverse ethnic and cultural groups. The foods of the Philippines are a symbol of the perseverance and adaptation of the islands. Their journey from traditional foods to the current palate dates back to the early 1500s during colonial rule. When the Spaniards colonized the Philippines, they instigated changes throughout economic, political, and, most importantly, cultural spheres. The Spanish colonists implemented new customs and traditions, primarily through catholicism. Because of this, holidays that were associated with food or fiestas were implemented into the new Philippines. Most special occasion meals like lechon or leche flan, eaten during the holidays, are rooted in Spanish colonialism. Furthermore, during Spanish rule, Filipinos were forced to adapt new ingredients and methods of cooking into their everyday lives. By the late 1800s, Hispanic dishes had become popularized all across the islands. Similarly, Filipino culture took on aspects of western culture during the Spanish-American War in 1998. To gain independence from Spain, the Philippines worked to prove their sophistication to bigoted American families through their hospitality. Filipinos were under the impression that Americans were there to aid them. As Megen Elias stated, “Food played an important role in Americans’ evaluation of the Philippines’ modernity and readiness for independence.” The complexities of Filipino dishes caused some Americans to scrutinize preconceived notions of the people. However, it is important to note the limitations of this source. The Americans’ intent was not to free the Filipino people or even help them. Americans fought in the Spanish-American war so that they may conquer more Spanish territory. Conclusively, America acquired the Philippine Islands in 1898, dumping the Filipino people back into this oppressive cycle. Nevertheless, Filipino culture would undergo another cultural shift. Soon, Filipinos catered to the western palate as well, integrating traditional Filipino flavors into these newfound western and Spanish-inspired dishes. Filipinos worldwide who have mastered the ability to craft these authentic, signature flavors using any ingredients have truly defined what Filipino cuisine is today.

Elias, Megan. “The Palate of Power: Americans, Food and the Philippines after the Spanish-American War.” Material Culture 46, no. 1 (2014): 44–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24397643.