The American Dream Instilled into the Filipino Household: An Oral History

Many Filipino Americans exude a sense of solidarity and loyalty to America, oftentimes even before immigrating. There were a series of factors that led America to have such a lasting impact on the islands. It seems that America was able to infiltrate almost all sectors both intimate and political. This created a group of individuals that, from the time of independence to the reign of Marcos, may not have had full access to the truth about political issues at the time. The political leaders of the post-colonial Philippines started to gain traction in the years leading up to Marcos’ rule, however, these tribulations fell on deaf ears in more rural parts of the islands. Some were unwilling to accept the negative effects of America, others did not even get the privilege of receiving such information. In the case of my grandpa, his Western ideals have always been present because of his father’s history with the U.S. military. Cut off from most major cities and flows of information, my grandpa depended on his father and his schooling to educate him on current events. However, in doing so, he developed a very pro-American mindset, one that embodied the American Dream. His life on the plantations new little discourse, only the need to provide for one’s family at any cost. During his final year of high school, his family was able to put funds together for him to access education in a major city: Manila. By the time my grandpa was 19, it was nearly his familial duty to find work in America in order to do the same, and financially aid his younger siblings. This was largely due to his father’s experience in Texas. His father always marveled at the benefits of America as an individual, but he never wanted his family to be there permanently, he only loved it because of what it offered his family back home. To this day, family will always come first for my grandpa. In the years leading up to the 1960s, many Filipinos, especially the working class, found that their loyalty resided with America because of America’s firm hold on Filipino politics, the military, and the public education system. America’s incentive was to keep the Philippines under its control even after they officially separated, which it enforced by painting itself in a more heroic light during a time when Filipinos were questioning America; In doing so, they unintentionally made America out to be a utopia, where Filipinos could allegedly access all the opportunities and economic benefits they had been deprived of.

America’s military presence in the Philippines acted as the bedrock for the integration of American ideals into Filipino homes. In 1898, America officially gained control over the Philippines. Previously, during Spanish colonial rule, Filipinos had little rights and occupied minimal jobs. They were fully suppressed under colonial rule so when America came with the proclaimed intentions of aiding the islands, they were in support. However, America did not view Filipinos as equals, but rather as people to indoctrinate with American ideals. Unlike the Spaniards, America implemented a “democracy”, although it did not function as democracy did in America. The ideals of democracy enticed many, even though this did not genuinely matter because the decision was not up to Filipinos. Once in control, America used this gilded image of itself to take advantage of many Filipino people and often used communities as pawns for American propaganda. During the WWII drafting, America extended its draft to Filipinos in exchange for dual citizenship and a taste of the promised land. Many Filipinos faced imbalances within the military, they did not get equal pay or benefits. However, loyalty to America was stronger than ever, as soldiers were often splitting their time between America and their own households. My grandpa recounts his father saying that as an American soldier, his title and position as such always came first, before the Philippines. His father glorified the West and his time in Texas. My grandpa speculates that this is because he was a humble and hardworking man who was not keen on complaining, especially when the results were bettering his family. In my grandpa’s home, there was not only a Western mindset but an understanding that America was their family’s main source of income, one way or another. As a family of nine, his father’s drafting and time in America were crucial, their only other source of income being his siblings’ part-time jobs. In this way, American loyalty crept into households and families across the islands until it became a widespread understanding.

American policymaking within the Philippines was often geared towards the financial benefit of America, sometimes these goals overlapped with the working or agricultural class of the Philippines, causing them to believe America was in favor of their betterment. For starters, the Filipino economy became highly reliant on their exports to America and other trade relations that America had set up. After the 1900s, the economy depended on agriculture within the islands. The Bell Trade Act allowed for a prosperous relationship between America and the Philippines. The act converted the peso into the dollar which in short, allowed trade to America from the Philippines to be free. America also promised to introduce new agricultural techniques, employed for efficiency. Unfortunately, these were underfunded and therefore not as useful as promised. However, the overall efficiency of production and harvesting was increased in the early 1900s. My grandpa was most certainly a beneficiary of this, and so was his community as he grew up in a place defined by their banana plantations. In bringing productivity and significance to agricultural workers, America gained the respect of many of the working-class communities.

Even after the islands were legally declared independent in 1946, America continued to occupy the islands, while also remaining present in cultures they had previously implemented. This is because of the slow fizzling out of American power, as they legally made all Filipinos into Aliens to the U.S. in 1934 with the Tydings-Mcduffie Act. Although this worked to benefit the Philippines’ path to independence, it also created more socio-political unrest. In labeling all Filipinos as Aliens to the U.S., the act created a legal distinction between these two identities, however, this only catered to American purity. Alongside this policy, America issued a transitional government called the Commonwealth. This was a 10-year plan set to help the islands transition into full autonomy. The fine print of this system was that every decision made by the Commonwealth had to be approved by America first, so the new system was not that different from the last. This consequence made it impossible for the Philippines to act freely because, without the consent of America, an action could not be made. This encouraged many rising Filipino political leaders to not only adopt American ways but to also prioritize America, especially economically, over their own country. This solidified America’s legacy, as the slow fizzling out of American power was not the clean break that was promised. The remnants would later not only influence political leaders but set the trajectory course for development.

America remained the dominant power within the islands until the Japanese invasion of 1941 when many Filipinos, if they hadn’t started to already, began to distrust dominant American ways. Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese invaded Filipino shores as well. However, at this time, the Commonwealth was still being controlled by the U.S. military. Given that America had been attacked just 10 hours earlier, the Commonwealth had little to do except stand idly by, waiting for orders. At this time, the formation of the Philipines as an independent entity was very weak and still in the works. Even excusing this fact, the Philippines was almost defenseless against Japan. By the time it had ended, the Commonwealth had barely even lifted an aircraft into the air. Most were shooting from the ground. After the damage had been assessed, many pointed fingers at America, in a blatant display of neglect. This became widespread proof for many that America did not have the people’s best interests in mind. There was an uptick in student protests and rebellion against the American way, which was especially prevalent in cities like Manila, Zamboanga, and Cebu. However, my grandpa had no recollection of these movements, even when attending his last year of high school in the city of Manila. This is where my grandpa’s story seems to deviate from the common one. He claims that the schools he attended never taught politics, they were mainly religious and language-based. In this way, my grandpa’s experience did not align with the denominate one, however, that is not to say that at this time, students weren’t rebelling and collectively questioning why American loyalty was being preached.

Public education, a system that America had established in the Philippines during their occupancy, remained heavily geared towards the West, which greatly influenced the new generation of Filipino people. Before America came, the Spaniards did not include Filipino people in their public education systems. With American colonialism, Filipinos were finally able to access public education, that was not just for elites. This was not a system that the people were eager to give up as America then left. However, not only did they keep it, but it remained unchanged. The main languages taught were still Spanish and English, excluding the native language, Tagalog. This is not to say that Filipinos were not working to rebuild Filipino solidarity and independence, but historically these efforts were put into predominantly cultural spheres, rather than economic, political, or educational systems. Throughout the 1930s the focus remained on this cultural sphere because many Filipinos felt they still had to prove to the world that they were not “savage” and that they were able to exist independently. The cultural aspects were also easier for activists and leaders to influence because many of the spheres were controlled by the Philippines’ Westernized government. For many children growing up in rural areas, the public school and their family was the only exposure they received to political issues. The news was often filtered through a pro-American lens, especially when it was not in the city.

Leading up to the 1960s, and Marcos’ election, the Filipino economy repressed job opportunities, making it difficult for low-income families to gain upward mobility. In the late 1950s, Espiritu claims that only a small percentage of graduating students were even able to be employed, and this was mainly college graduates. My grandpa stressed this, and why this ultimately led him to immigrate right out of high school, “If you are down, there is no going up in the Philippines.” For him, there was a mutual understanding that his only option was to travel to the U.S. His older brothers all had jobs and his younger siblings and parents needed support. He applied for a work visa almost immediately. He said that there was no future for him in the Philippines and his family urged him to move to the U.S. His father never wanted him to start a family here, he only wanted my grandpa to have a future and to benefit the family in the Philippines in a way that staying in the islands could not. He said that upon coming to the U.S. many of the immigrants on his boat had the same background, they were low-class children, looking for money to bring home to their families.

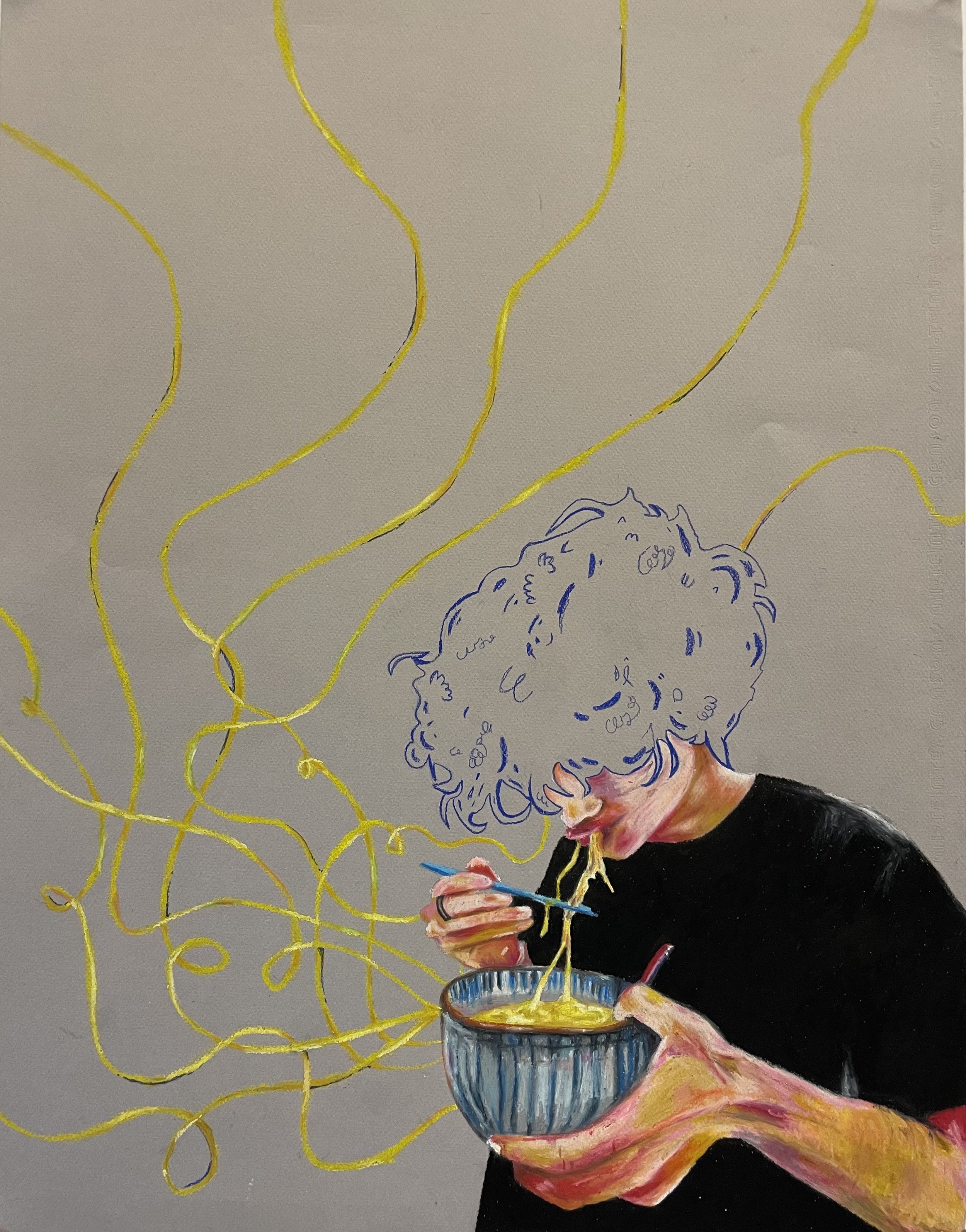

Many graduates’ only option seemed to be immigrating to America, in pursuit of the American Dream, for the betterment of themselves, but also their families. America’s everlasting presence in the Philippines showed how America intentionally played the good guy in the Filipino eye, but unintentionally advertised America as a haven for migrants. The West became this beacon of hope in the midst of a near-economic collapse and financial insecurity. In defining America as the savior, and thereby destroying Filipino autonomy, America could then create a world where the Philippines could not support its own people. This fueled one’s desire to seek opportunity across seas. Thereby, altering the defining factors of Filipino families and dynamics. Because this mindset had been indoctrinated into my grandpa, he chose to work in America and then eventually start a family there. To him there was no other option, it was inevitable.

Although my grandpa believes in American ideals and that this path was out of his own free will, his story corroborates one that suggests the influence of censorship, colonial powers, and propaganda. Upon coming to America, he states that it was a lot different than he pictured. He thought he would find work instantly, but most people told him he would not find one without attending college first. He also attests to the unwelcoming environment and political turmoil he became a part of. A lot of his stories uncover the unruly truth about immigrant opportunities and treatment in the U.S. He faced discrimination while working multiple jobs. He did not visit his family as often as his father did and his family rarely visited him. He worked jobs that uncovered the underbelly of corporate America. One was his job at Sealand, where he would receive shipments of dead bodies back from Vietnam, during the war. He said that many people around him often quit because of the various working environments. Even still, my grandpa does not regret his decision to come here because his idea of the American Dream centered around providing for one’s family, and since he was able to do that, he was happy. He never received the financial freedom that many middle-class Americans access today. However, most impressively, over the span of 20 years, he was able to pay for all of his siblings, except the eldest daughter, to come live with him in America, and eventually, he helped them get jobs and establish their families in the U.S. He has always known hard work, and is tough enough to withstand discrimination, so to him, this was the epitome of the American Dream: to work and to be rewarded, to be able to raise children in America, with access to the college education he never had.

Primary Sources

Bucoy, Freduardo. Oral Interview. Conducted by Audrey Green. November 22, 2023.

Orendain, Antonio E. II. “Zamboanga Hermosa.” Filipinas Foundation, Inc. 1984.

Secondary Sources

Goodman, Grant K. “The Japanese Occupation of the Philippines: Commonwealth Sustained.” Philippine Studies 36, no. 1 (1988): 98–104.

Jose Veloso Abueva, “Filipino Democracy and the American Legacy,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 428 (1976): 114–33.

Norman G. Owen, “Philippine Economic Development and American Policy: A Reappraisal,” In Compadre Colonialism: Studies in the Philippines under American Rule, edited by Norman G. Owen, 103–28. University of Michigan Press, 1971.

Resil B. Mojares, “The Formation of Filipino Nationality Under U.S. Colonial Rule,” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 34, no. 1 (2006): 11–32.

Rick Baldoz, “The Third Asiatic Invasion: Migration and Empire in Filipino America, 1898-1946,” NYU Press, (2011): 194-236.

Yen Le Espiritu, “Leaving Home: Filipino Migration/Return to the United States,” In Home Bound: Filipino American Lives across Cultures, Communities, and Countries, 23–45. University of California Press, 2003.